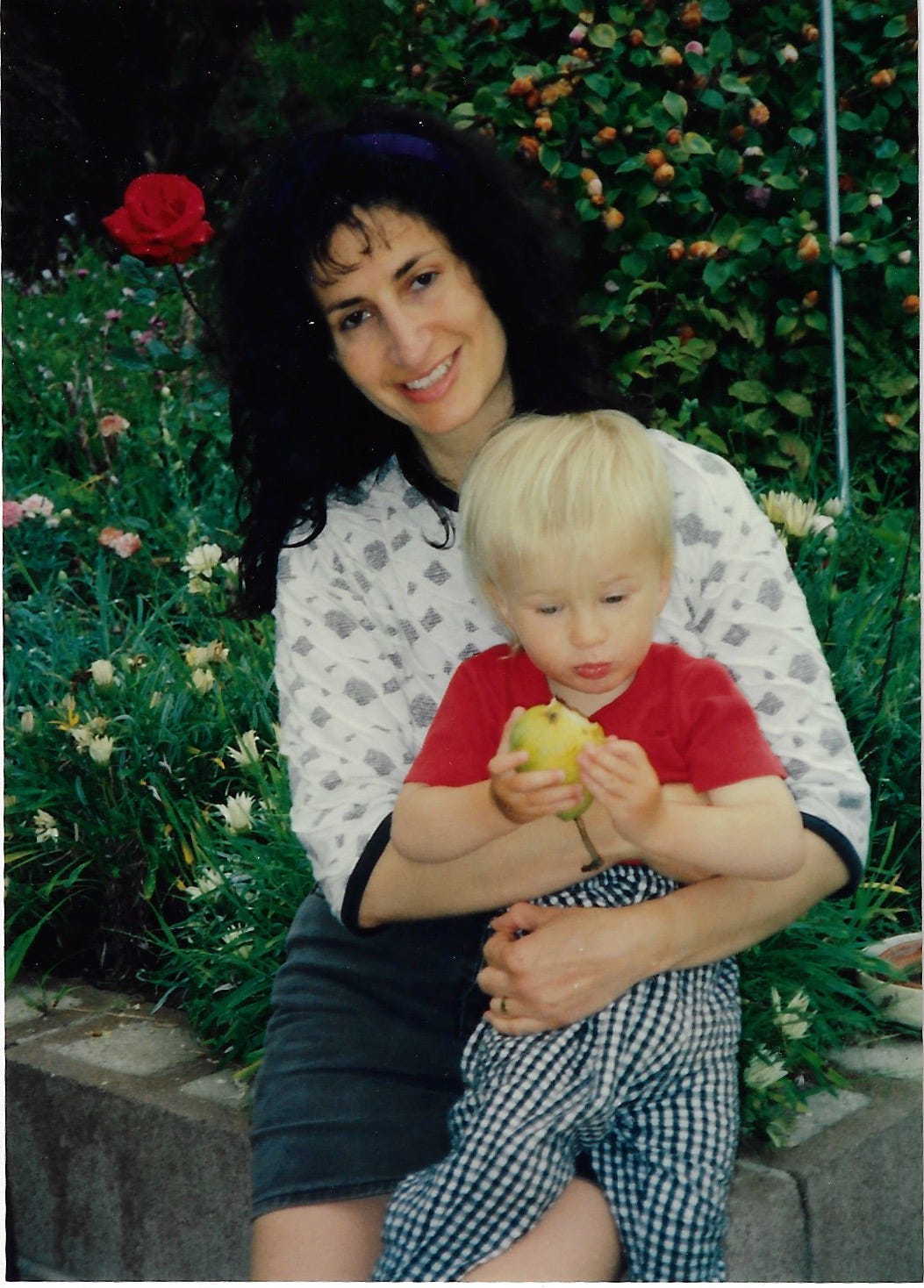

The Bread My Mother Gave Me

She apologized that it was

probably stale—but how could it not be,

when handed to me

in a dream, on a visit

from the afterlife?

It had honey baked into the middle

and was more delicious

than any bread

I’d ever tasted.

I told her how grateful I felt

for this sustenance from her,

however late it came—

for the loving way she looked at me

across that distance

between life and death,

A hand’s breadth between us

as I received

that holy bread

and ate to fill

that hungry place

inside me.

Copyright ©️ 2024 by Barbara QuickAnd the tale continues…

Fernando and Gloria were a hard act to follow. But Francisco Andreas—a lanky nineteen-year-old Colombian soon known to us as Paco—did a pretty darn good job. Over six feet tall, with skin the color of tea, raisin-black eyes, a perfectly round head and a thousand-watt smile, Paco looked like nothing so much as an animate gingerbread man. He spoke only a few words of English, but made up for his language deficits with a seemingly endless capacity to laugh and smile.

The language school expected host families to provide food for the students’ self-serve breakfasts and cooked dinners every night. On weekends I was supposed to provide breakfast, lunch and dinner; but it rarely worked out that way. Between friends, relatives, and sightseeing excursions organized by the school, all my boarders had spent their weekends away for the most part. Paco had a brother and sister-in-law living in San Francisco, and could be relied upon to split every Friday night.

As much as I like cooking, I dislike doing it just because I must, especially if I’m tired or there’s an uninspiring array of ingredients in the cupboards and fridge. Colby showed enormous sensitivity to my need to balance nights of cooking with nights of being taken out. He tucked in appreciatively whenever I invited him to supper, but he just as often took me out to eat, bringing good-quality fast food for Paco if I didn’t have leftovers on hand.

Good cooks are really the people who should be taken out—not only as a reward for their achievements in the kitchen, but because a well-prepared meal that’s the product of someone else’s imagination never fails to excite new enthusiasms and ideas.

***

Learning to cook was for me an act of teenage rebellion against the role model provided by my dear departed mother, who came into her marriage at the tender age of twenty with absolutely no kitchen skills at all. Although my grandmother was actually a decent cook, she worked long hours in the small Manhattan grocery store she and my grandfather owned with my great Uncle Leon. My mother, an only child, was left in the care of a maid who’d been taught by my grandmother to cook chicken soup and other Eastern European standbys. But none of this lore was passed on to my mother, whose ineptitude was the cause of over twenty years’ worth of caustic reproach, criticism and occasional violence on the part of my dad. Over the years she learned, either from my grandmother or from friends, how to make two entrees quite well: stuffed cabbage and brisket, both cooked in a Dutch oven. Otherwise, her standard approach to anything that had once been alive was to broil or boil.

Almost every piece of vegetable matter that passed our lips had been canned or frozen at some point in its existence. As it has been said elsewhere, post-war housewives were simply in love with high-tech culinary shortcuts. The commercial canning and freezing operations that were no doubt a blessing to families living in the snowbound Midwest were nonetheless blithely patronized by housewives such as my mother living in Los Angeles, surrounded by some of the prime fruit-and-vegetable-growing farmland in the world.

Until I had my own garden, I thought that beans grew as the limp green, tasteless tinsel my mom heated up out of the can, and that lima beans were gray. We ate canned tomatoes served as a side vegetable with rice and previously frozen breaded sole, or defrosted and boiled greenish-yellow broccoli (which used to make me gag), side by side with broiled chicken and whipped potatoes. Mom projected the idea that fresh vegetables were—well—dirty. She would scrub the potatoes under vigorously running water until the skin started wearing through. On the few occasions when she used fresh mushrooms in a recipe, she would flay them with the labor-intensive zeal of a medieval torturer until they shone bright white and helpless on the kitchen counter.

Much to our salvation, both mom and my grandmother always served either a salad (iceberg lettuce, carrots, celery and tomatoes), a halved avocado drizzled with lemon juice or half a grapefruit with a maraschino cherry in the center before the meal. I have since learned that this was thanks to the public health nurses in the nineteen-teens and ’twenties who were sent out to the tenements of New York City to visit the newly arrived Eastern European immigrants—people who were used to eating only pickled and preserved fruits or vegetables during the long months when nothing fresh could be procured. These government representatives schooled the new Americans, eager to fit in, about the importance of including at least some fresh fruits and vegetables in their families’ diets year ’round.

In all fairness to my mother, I think it must have been terribly oppressive for her—a person who disliked cooking, who had absolutely no interest in cooking and took no pleasure in it—to be expected to plan, shop, cook and then clean up after breakfast, lunch and dinner for four, later five, people seven days a week. My father would only rarely—perhaps once or twice a year—take my mother out. I have pleasant recollections of dinners at my grandmother’s house, but hardly any memories at all of going out to a restaurant en famille.

Food and cooking simply didn’t have the sex appeal in the fifties and sixties that they do now. The phrase “celebrity chef” was an oxymoron. My mother would have been far better off, and far happier, if she’d been a career woman, leaving my brother and me in the care of a babysitter (my sister didn’t enter onto the scene, somewhat as a surprise to us all, until my brother was fourteen and I was nine). If Mom had worked, perhaps money wouldn’t have been the tremendous problem that it was the entire time I was growing up. Dad might have been a little more relaxed, and a little less overwhelmed, knowing that he didn’t have to be the sole breadwinner for his family. Mom might have been emotionally present for us, instead of checked-out, comatose style, if she’d had a life outside our home.

But with less than two years of college, with an intense lack of confidence and barely any work experience at all, Mom sat at home feeling inadequate, miserable and lost. And Dad went to work every day feeling robbed of the chance to be an artist or a surgeon, and cheated because he was married to a spoiled, lonely girl from the Upper West Side who expected her husband to take care of her. Inadequately nurtured (although in different ways), both of them wanted a parent masquerading as a spouse. Instead, much to their bitterness and disappointment, they got each other.

Both my brother and I were terribly thin as children, and I was regularly accused of picking at my food or “eating like a bird.” This was in large part due to genetics; but I’m sure that the missing sense of culinary pleasure and excitement also played a role. Dinners were an emotional ordeal, which my mother, brother and I colluded to orchestrate so that we could avoid a blow-up on the part of Dad. His gin and Bubble-Up, his plate of salted pretzels and Jack cheese cut into neat rectangles, simply had to be ready for him the minute he walked in the door. I’m told that my first word was “gin.” The table had to be set carefully. Any piece of flatware that had tooth-marks in it from the garbage disposal was given with tacit permission to my mother. She wouldn’t care, whereas for Dad it might serve as the occasion for a humongous display of temper.

I do remember one stellar evening when my father brought home some Alaskan salmon that had been used in one of his photo shoots for the grocery-store chain where he worked as a graphic designer. Dad cooked the fish over coals on a hibachi in the atrium of our Orange County tract home. We’d just moved in, and the place had an odd feel to it, as if other, happier people were supposed to be living there. My mother used to insist that it was a beautiful house and that she loved it. For me, it was nothing short of a prison.

That salmon is the first food I can remember truly savoring—and it seems somehow significant now, looking back, that my dad cooked it rather than my mom. The taste of the fresh, firm fish, the mixed sensation of wood-smoke and sea, the melting tenderness of the sunset-colored flesh have stayed with me all these years.

***

Stewart took Kyle south to visit his mother in San Diego that first Thanksgiving after we were separated. Colby took me to Santa Cruz for the holiday to meet his youngest brother, Marc, and partake in a feast that someone else was cooking.

We were not yet two months into our relationship then, but there was a comfortable sense of ease to it already. I felt a bit conscious of being the eldest, as well as the only parent, in this household of bachelor musicians and bad boys. Marc himself was the eldest and most responsible of his crew. Warm and welcoming, he echoed many of Colby’s endearing qualities and cooked much of the dinner himself. His lusciously beautiful girlfriend, Evelina, was young enough to be my daughter. But we were both taking samba classes, which gave us a common point of reference, and she didn’t seem to treat me as anything other than a contemporary. This was an atmosphere in which I didn’t feel drawn to talk overmuch about my age.

It was an anxious time as well: I had a little more than thirty days to find and move into a new house or apartment, but I still had no leads. Probably out of a sense of stress, I’d developed a bad cough again. It was the winter of El Niño, but the weather that Thanksgiving was warm and mild. Colby and I motored down to Santa Cruz in the Sterling, which was proving itself to be a fine old workhorse of a car.

We were shy about doing too much of the “couple” thing. Colby spent his time playing chess with Marc’s friends, many of whom he’d known for ages. I was reviewing a French translation a dear friend of mine was making of my first novel. After dinner, a group of us that didn’t include Colby decided to walk down to the beach.

It was still light when we started out. There were four of us: Evelina, Marc’s good friend Tony, Tony’s wife Pam and myself. Evelina and Pam wound up walking at a slightly brisker pace than Tony and I were maintaining, eventually losing us. Tony kept me amused and disarmed with his clever but caustic patter. It was soon dark and I ended up telling him pretty much my whole life story. At the end of the walk, after we’d all gotten lost and stayed away at least an hour longer than we’d intended, Tony told me that he and Pam had a five-bedroom house in Kensington that was about to become available for rent. If I wanted to expand my boardinghouse operation, I’d be welcome to give it a go. The house would be empty by January first—which was exactly my deadline for being out of the old place.

Kensington is one of the few areas in the East Bay that has a really good public elementary school. I kept thinking to myself, if Stewart hadn’t taken Kyle to his mother’s for Thanksgiving, if his mother didn’t so ardently dislike me, if Colby hadn’t invited me to his brother’s, if Tony hadn’t gone to that consciousness-raising workshop with Marc in the late ’80s, if Tony and I hadn’t gotten separated from Evelina and Pam, if I hadn’t told him my life story, if we hadn’t gotten lost and walked an hour longer than we’d meant to…

But maybe it would have happened anyway, somehow, in the way that such things are squeezed through the dark and narrow birth passage of the cosmos. The house was a gift, tied up with ribbon, placed at my feet. Five bedrooms, two-and-a-half baths: exactly what I’d wished for. A mile away from a wonderful and free elementary school. A beautiful and safe neighborhood, and landlords who were fully sympathetic to my cause.

I talked on the phone for the first time on that visit to Colby’s mother, who greeted me with an irresistible warmth and enthusiasm. Sue Ellen, the promiscuous bartender, had laid the ground for me there: Colby’s mom was so relieved to find her son hooked up with someone more ladylike and—well, I guess—conventional. There was also great cement to be found in the fact that she’d read my first novel and really liked it.

So all of a sudden, I had a house, a great school for Kyle, a boyfriend who loved us both, and the mother out-law of my dreams. After the free fall of the past year, it looked as if Kyle and I would be landing on our feet.

Let’s Not Kid Ourselves: Food Is Love

Cranberry Scones

Set the oven to 375. Measure out 2/3 of a cup of buttermilk or plain yogurt, and mix together with one large egg.

Sift 3 cups of unbleached flour together with 4 teaspoons baking powder, 1/2 teaspoon baking soda, and 1/2 teaspoon salt. Grate into this mixture one stick of frozen sweet (unsalted) butter. Toss with a fork or rub together with your fingers, as you prefer—but do it fast. The idea is to coat the little pieces of butter with the flour mixture.

Add one cup of dried cranberries. (I find that the ones sold in bulk at produce stores tend to be plumper and nicer in general than the ones sold in packages.) With the cranberries, throw in half a cup of sugar and about a teaspoon of freshly grated orange peel. Stir lightly with a fork, then add the buttermilk mixture. Keep stirring just until things start sticking together.

This is the part that’s a little tricky. Quickly gather the contents of the bowl into a ball—and then press your still-flaky dough onto an ungreased baking sheet, patting it together until you have a circle that’s about an inch high. Touch the dough with your hands as little as possible.

Use something rigid and plastic (if you’re using nonstick bakeware, a good idea) to divide the circle into eight wedges. Separate these on the baking sheet, stick it in the oven, set your timer for 20 minutes, and wait for the magic to begin.

It’s fun to find an excuse to go outside for a little bit so that you can walk into a miraculously delicious-smelling house.

When the scones are golden, they’re done. Brush them with a little butter, and sprinkle this, if you want to, with some turbinado sugar. Remove to a wire rack, but serve them while they’re still fragrant and warm.

Baking something that will make someone feel loved and valued is certainly one of life’s more accessible miracles. If you get up earlier than usual to do it, so that your loved one smells the heavenly scent of your labors first thing upon waking, you have made the world a kinder, gentler place, perhaps even for generations to come.

Don’t expect gratitude if the object of your love and labor happens to be a child. This is a slow-ripening miracle: it may be many years before your child understands the meaning of your gesture or even says thank-you. This is one case where gratitude needs to ripen in its own sweet time.

Give because you are filled with love—out of your own hard-earned sense of abundance. And know that you are giving the gift of fresh-baked scones not only to your child but also to the child you once were.

.

Gorgeous photo!!

I too love all the parts of this offering. Thank you

Loved everything about this installment.